In 1986 the United Church of Canada issued an Apology to Native Peoples that began: "Long before my people journeyed to this land your people were here and you received from your Elders an understanding of creation and of the Mystery that surrounds us all that was deep, and rich, and to be treasured ..."

This was the first acknowledgement that Canada had been teaching a history that was not true.

In 1998, the United Church went further by issuing an Apology to Former Students of United Church Indian Residential Schools, and to the Families and Communities. It included these words: "On behalf of The United Church of Canada, I apologize for the pain and suffering that our church's involvement in the Indian Residential School system has caused. We are aware of some of the damage that this cruel and ill-conceived system of assimilation has perpetrated on Canada's First Nations peoples. For this we are truly and most humbly sorry ..."

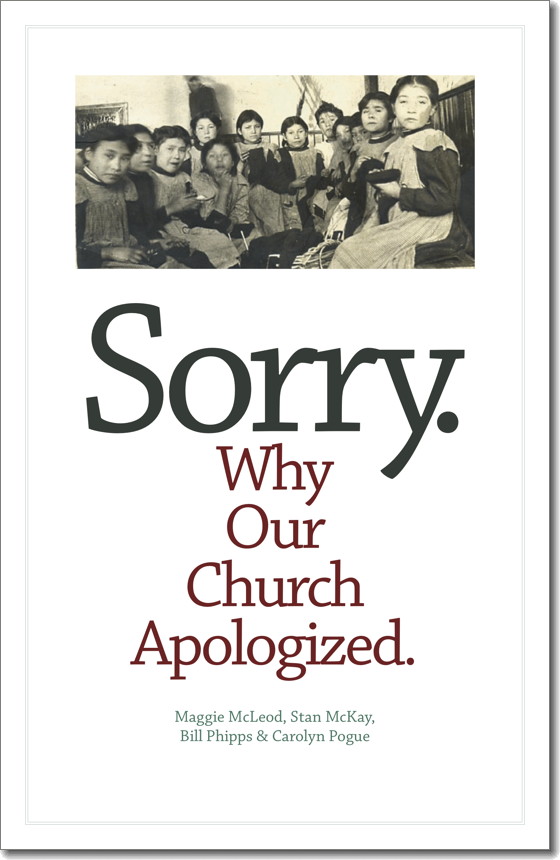

The just-published book, Sorry. Why Our Church Apologized., tells how the church became involved in the schools and how it is that the church saw it must withdraw from the system, and become involved in learning and healing.

Sorry was written by four members of the United Church of Canada who have experience in bringing together Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, both inside and outside their church. Sorry was written as a response to invitations from elementary school students in Alberta who asked, "Why were churches involved in running these schools?" and "What did it feel like to apologize?"

The authors:

Reverend Maggie McLeod is from Peepeekisis First Nation. She now works for Aboriginal Ministries, United Church of Canada in Toronto.

Very Reverend Stan McKay was born on Fisher River Reserve and attended Birtle Indian Residential School, Manitoba. He is a retired United Church minister and former Moderator.

Very Reverend Bill Phipps from Toronto now lives in Calgary, Alberta. He is a retired United Church minister and former Moderator who is currently active on Climate justice issues.

Carolyn Pogue is the author of 14 books and writes "Sightings," a blog for The United Church Observer.

Published by Wood Lake, August 1, 2015

ISBN 978-1-77064-803-6

5.5" x 8.5" Paperback, 26 pages, $9.95

From the back cover:

Sometimes it is not so hard to say sorry. Sometimes it is very hard. What matters most is meaning it when you say it.

You likely know what it's like. You likely remember a

time when someone said sorry to you. Maybe you've heard

about a church saying sorry as well.

One surprising year, the United Church of Canada

people did just that. The church has members in

Newfoundland, Yukon and everywhere in between. The people who

attend have Asian, Indigenous, African and European ancestry

Canadians are from everywhere!

This is the story of why the United Church

people apologized for the suffering caused by

Indian Residential Schools..

The book is available in 4 formats:

As a print book, for $9.95 per copy. To order go HERE.

As a downloadable PDF, which can be printed. To download, click HERE.

As a web flipbook - see immediately below.

As a single web page - alse see below.

SORRY. WHY OUR CHURCH APOLOGIZED.

Contents

The Early Connections

Treaties and Residential Schools

Growing Awareness and the Sorry Feeling

From Sorry to Right Relations

Some Things to Think About

Appendices

Dedication

For the Children of Yesterday,

Today, and Tomorrow

Sometimes it is not so hard to say sorry. Sometimes it is

very hard. What matters most is meaning it when you say it.

You likely know what it's like to say sorry and mean

it. You likely remember a time when someone said sorry

to you. You might remember hearing news that a car

manufacturer or a food producer said sorry about a big mistake.

Maybe you've heard about a church saying sorry as well.

One surprising year, the United Church of Canada

people did just that. The church has members in

Newfoundland, Yukon, and everywhere in between. It's a Canadian

church and the people who attend have Asian, Indigenous,

African and European ancestry Canadians are from

everywhere! The United Church is one church made up of many

congregations. Possibly there is a United Church of Canada in

your own community.

This is the story of why the United Church people

apologized.

The Early Connections

Soon after Confederation in 1867, the Canadian

government had an idea of how to build up our country. They

wanted Canada to stretch from sea to sea to sea, and they wanted

to fill the land with settlers. They hoped to have a nation

of people who would make farms, start ranches, dig mines,

and build factories. The government people thought it would

be a good thing to encourage everyone to be the same; that

is, like them. They wanted Canadians to speak only English

or French. They wanted everyone to honour the Queen of

England. The government people wanted all people to

dress, think, and worship God as they did, and enjoy the

same sports, music, and art.

But the Indigenous peoples who lived in Canada

didn't fit with those descriptions. They dressed differently.

Women did not lace themselves into corsets or wear stiff

leather shoes. Men did not work in offices or factories.

Indigenous peoples enjoyed foods from the land that were

different. They had spiritual traditions that honoured Creator God

and their connection to land and to all life. They spoke

many different languages, rather than English or French.

The government saw these differences as a problem

to solve. They wrote treaties. A treaty is an agreement

between nations. Indigenous peoples who signed the treaties

believed that they were peace agreements between nations that

would benefit everyone. The government believed that the

treaties gave them special power over Indigenous people.

From the beginning, these different understandings about

treaties caused many problems about how to live together.

The government forced Indigenous peoples in much

of Canada to live on reserves. The government created laws

that gave themselves many advantages. One law prevented

Indigenous people from voting in Canadian government

elections. One law divided "Status Indian" from "Métis" and

gave different rules for each. Laws controlled how

Indigenous people farmed, sold produce, or made a living. One law

made it a crime for people to leave reserves without

permission. These laws were eventually changed. But one law lasted

a long time. It caused huge problems. It concerned children.

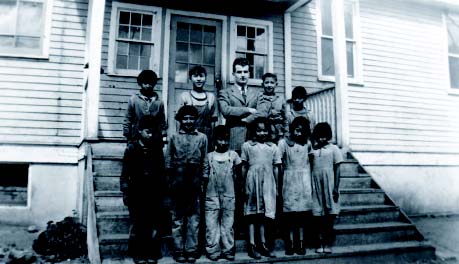

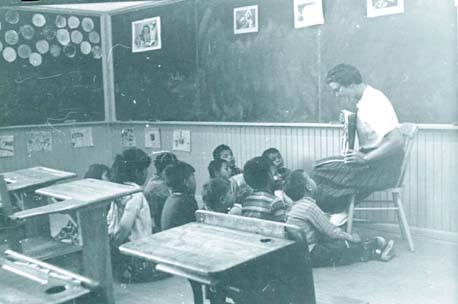

Whitewood, Saskatchewan, circa 1940, UCCA, 93.049P/116

Norway House, Manitoba, circa 1910, UCCA, 93.049P/1261N

Treaties and Residential Schools

Treaty agreements included apromise by government

to provide education for Indigenous children. The schools

were meant to make the children be like the settler people.

Some were day schools. One hundred and thirty were

residential schools. This meant that children had to leave their

parents, their homes, and their pets for ten months of each year

and live at the school. Over the generations, about 150,000

children attended these schools.

The government asked the Anglican, Presbyterian,

Roman Catholic, and Methodist churches to run the

schools. (In 1925, the United Church of Canada took over the

responsibility for Methodist and some Presbyterian schools.)

The Roman Catholics ran 79 schools, the Presbyterians ran

two, the Anglicans ran 36, and the United Church ran 16.

The last United Church residential school closed in 1969.

The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996.

The government wanted the Indigenous children to

be taught so that they would forget their own languages,

stories, dances, and songs. They wanted the children to

forget their understanding of how God was present within

them and within their communities. In essence, they wanted

the children to forget their identities. At thattime, the

church people believed that assimilation was a good thing and

that they were helping Indigenous peoples "move into the future."

The government gave money to the churches to

hire teachers and buy food, school desks, clothing, and so

on. Church people also sent money to the schools. But

usually there wasn't enough money to run the schools properly.

Students often had to farm or garden to raise their food.

They were often hungry. School shoes and clothes often didn't

fit properly or were not warm enough.

Some teachersand supervisors were kind; they

wanted the best for the students. Some were mean. Some wrote

official letters to the government saying that the

residential schools were a bad idea. The letters told stories

ofneglect and abuse. Unfortunately the letter writers were

not believed,and some were even fired from their jobs.

For generations, Indigenous children were forced to

leave their families to attend residential schools. Some

travelled great distances by ship, truck, or railway. Some

Indigenous children died at the schools; nearly 6000 never went

home again. Although some went on to live happy lives, many

felt ashamed, angry, or sad for many years. Experiences of

childhood last a lifetime.

Most Canadians did not know about these schools

because the schools were located in places far removed

from larger towns and cities. Canadians did not understand

or didn't know what was going on. Not many people

thought about howwrong it was to take children away from

their parents, grandparents, and communities.

Over the years, non-Native church people began to

catch glimpses of what had been lost by not honouring the

culture and wisdom of Indigenous peoples. They also began

to understand how racism was not something happening

just in other countries; it was also right here in Canada.

Along with other churches, the United Church took part in

en-vironmental and social justice actions. For example

church people stood against the proposed Mackenzie Valley

pipeline because they learned from the Dene that the

pipeline would be dangerous to Earth and to the communities

along the pipeline route. Through relationships like this,

non-Native church people began to work with and learn from

In-digenous peoples, both inside and outside church.

Norway House, Manitoba, between 1916 and 1921, UCCA, 93.049P/1269N

Norway House, Manitoba, circa 1950, UCCA, 93.049P/1243

Brandon, Manitoba, 1902, UCCA, 93.049P/1363bS

Red Deer, Alberta, 1919, UCCA, 93.049P/855N

Growing Awareness and the

Sorry Feeling

By 1986, United Church people were ready to say

sorry for not listening before. The United Church of Canada

leader, Moderator Reverend Bob Smith, said these words at a

national church meeting in Sudbury, Ontario:

"Long before my people journeyed to this land your

people were here, and you received from your Elders an

understanding of creation and of the Mystery that surrounds us all

that was deep, and rich, and to be treasured.

We did not hear you when you shared your vision. In

our zeal to tell you of the good news of Jesus Christ we

were closed to the value of your spirituality.

We confused Western ways and culture with the

depth and breadth and length and height of the gospel of

Christ. We imposed our civilization as a condition for accepting

the gospel.

We tried to make you be like us and in so doing we

helped to destroy the vision that made you what you were. As a

result you, and we, are poorer, and the image of the Creator

in us is twisted, blurred, and we are not what we are meant

by God to be.

We ask you to forgive us and to walk together with us

in the Spirit of Christ so that our peoples may be blessed

and God's creation healed."

When Reverend Smith said those words to Elder

Edith Memnook, she hugged him and said, "Thank you. I've

waited my whole life to hear those words." Yet she did not say,

"We forgive you." She and the Elders wanted to know more

about what the church meant by sorry. She wanted to know if

non-Native church people would repent, which means to

turn away from what is harmful and turn toward what is

good. Elder Memnook said that she and other Indigenous

peoples in our churches would help us. This began a very

exciting time to be in the United Church.

Red Deer, Alberta, circa 1900, UCCA, 93.049P/839

Chilliwack, British Columbia, circa 1920, UCCA, 93.049P/419

From Sorry to Right Relations

Non-Native church people went to workshops to learn

about Native spirituality. They began listening. They learned

about the effects of residential schools. They read books.

They watched videos and films about living in right

relationships with people, Earth, and all beings. They sat in circles,

listening to one another and working together to make

things right. They raised money for the church Healing Fund.

Indigenous communities use this very important fund to

reclaim culture and language that were lost during their

years at residential schools.

In 1992, the elected church leader was Moderator

Reverend Stan McKay, from Fisher River Cree Nation,

Manitoba. He had attended a residential school, and he had been

a teacher before becoming a minister. He knew that text

books and literature did not contain the whole truth of

Canadian history. He helped the United Church learn a bigger history.

Willie Blackwater was sent as a child to the Port

Alberni Indian Residential School on Vancouver Island. In 1994,

he said, "Canada needs to know what happened in the

school." It takes courage to speak out and let others know that

something is wrong. Willie's bravery led him to tell stories of

how frightened he was as a child because of the abuses he

experienced, and how that affected him even as a grown-up.

Willie went to court. He wanted a judge and jury to know about

these stories. Newspapers wrote articles about his testimony.

Radio and television reporters spread the story. Then other

brave former students began to come forward to tell their

stories too. The stories were very hard to tell and very hard to hear.

People across Canada were shocked. What would it

be like to have our children taken away? Did our

government really do this? Were the churches really involved? Were

the stories true? Were the schools so terrible? Did students

actually die at these schools?

Sometimes when we hear a scary story, we want to

cover our ears. If a story makes us feel guilty, we might

become angry. If we think that the truth of that story will cause

us to lose something precious, we might say that the

storyteller is lying. But sometimes, when stories are hard to hear,

we just feel sad and want to listen.

When churches started hearing all the stories about

kids being hurt, hungry, or beaten, people felt sad about all

of those things. No one wanted to believe that United

Church people had helped run schools that hurt families and

children. But we had to believe it because it was true.

Church people remembered how Jesus taught that the truth will

set us free, and we wanted freedom from sadness, guilt,

and anger.

The United Church people believed that they

especially needed to say sorry for hurt caused by these schools. In

1998, the elected church leader, Moderator Reverend Bill

Phipps, delivered these words:

"On behalf of the United Church of Canada, I apologize

for the pain and suffering that our involvement in the

Indian Residential School system has caused. We are aware of

some of the damage caused by this cruel system of

assimilation. We are truly and most humbly sorry. We are sorry that

some students were abused in these schools ... We know that

many within our church will still not understand why each of

us must bear the scar, the blame, for this horrendous period

in Canadian history. But the truth is, we are the bearers of

many blessings from our ancestors, and therefore, we must

also bear their burdens ..."

Since then, whenever they are invited, Moderators,

former Moderators, and other church leaders visit communities

to listen, learn, and offer the Apology in the hopes of

building the type of relationship God wants for us.

That is why the United Church people said sorry. That

is why other churches have said sorry too. We are part of

a long history of misdeeds that hurt many of the people

whose ancestors welcomed settlers to this land. Church people

want to live in right relationship now. This means living with

respect, wisdom, love, humility, truth, honesty, and courage.

By 2007, there were more and more law suits by

former residential school students against the government and

the churches. How could the government and the churches

settle these? The court brought together Indigenous

people, church and government representatives, and lawyers to

find a solution. They reached "The Settlement Agreement."

This laid out a plan to create a Truth and Reconciliation

Commission. The Commission's tasks were to make sure that

Canadians could learn the true history of our country and

to find ways to reconcile. To reconcile means to make peace

or to bring back together again.

In 2008, the government of Canada invited Inuit,

Métis, and First Nation leaders to Ottawa. On June 11, in front

of everyone in the House of Commons (in fact, in front of

all Canada), on behalf of the government, the prime

minister also said sorry. Many church people were present to

witness this historic event.

From 2009 until 2015, the Truth and

Reconciliation Commission travelled all around Canada. Chief

Willie Littlechild, Dr. Marie Wilson, and Justice Murray

Sinclair served as commissioners. Their job was to listen to

stories about what happened in the residential schools. They

listened to thousands of former students, teachers, and

workers. The United Church of Canada helped to support

this important work so that everyone would know the true

history of our land.

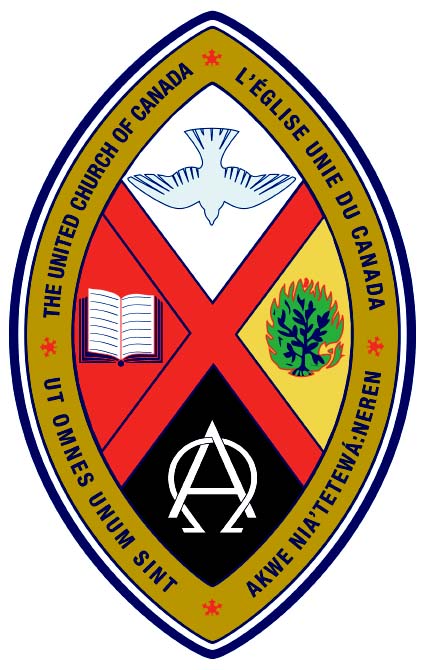

In 2012, Aboriginal ministries in the United

Church asked that the church crest be changed. The new crest

has the colours of the medicine wheel and includes the

Mohawk phrase Akwe Nia'Tetewá:neren (aw gway nyah day day

waw nay renh), which means "all my relations." These

changes help to show that the church respects Indigenous peoples.

Saying sorry is one step in the healing journey

for Canada. This is an exciting time for our country. The

next step is up to each of us. We are all in this together.

Some Things to Think About

What do you do when someone apologizes to you?

How can you tell when an apology is real?

What did Jesus say about sorry?

What do you do after you say sorry?

How do you celebrate National Aboriginal Day in your community?

Appendix 1

A letter from Stan McKay,

teacher, ordained minister, former Moderator of the United Church of Canada,

and former Residential School student.

My name is Stan McKay and I am a Cree person. Growing

up on the Fisher River Reserve, along the western shore of

Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba, our family made our own living

65 years ago. My mother had a garden, she milked a cow,

and we had a few chickens for eggs. She sewed our clothes,

and our neighbor made beaded moosehide slippers and mitts

for us to wear. We had no road into our village, but there was

a small store where we could buy flour, salt, tea, and oil

for our lamps. My father was often away from home

fishing, hunting, and trapping. He built the small log houses we

lived in. We lived near my grandparents and we had many

relatives living nearby.

I walked two kilometres to a school that my parents

had also attended. It was near a mission church that became

a part of the United Church of Canada. I knew my

grandmother and grandfather had spent their entire childhood

in a residential school but they never talked about it. When

I finished grade eight in the Fisher River School, I was told

I had to go to a residential school, which was 500

kilometres away. I was there for five years. It was a time of great

loneliness and I had some very painful experiences.

Even after spending most of her childhood in a

residential school, my grandmother was an active member of

the United Church, and she encouraged me to become a

minister. Her name was Louise and she taught me about

being respectful of all people. She and other members of my

family helped me survive the residential school experience,

but healing is a lifelong journey.

I became a school teacher after I left the residential

school and I taught for three years in Cree Indian day schools

in northern Manitoba. Then I returned to spend six years

in university, and in 1971 I became a United Church

minister. I returned to work in Cree United churches in

Manitoba, including seven years in my birthplace at Fisher River.

In 1991 friends asked that I let my name stand in

nomination for the position of Moderator of the United Church

of Canada. I was elected as Moderator in August of 1992.

I learned that many of the United Church

congregations did not know about Indigenous peoples and did not

understand how we feel inside. Many people wanted to change

us to be like them, but we have our own stories and ways

of prayer.

My dream for children today is that you may learn

to care for each other and understand that we are all related

to each other. The United Church crest now has "All My

Relations" printed on it, which means that we are related to

each other and to all of creation. There is great joy in sharing

life with thanksgiving and I wish you would dance on the

earth in large circles that include everyone.

Appendix 2

Apology to Former Students of

United Church Indian Residential Schools, and to their Families and Communities.

As Moderator of The United Church of Canada, I wish

to speak the words that many people have wanted to hear for

a very long time. On behalf of The United Church of

Canada, I apologize for the pain and suffering that our church's

involvement in the Indian Residential School system

has caused. We are aware of some of the damage that this

cruel and ill-conceived system of assimilation has perpetrated

on Canada's First Nations peoples. For this we are truly

and most humbly sorry.

To those individuals who were physically, sexually,

and mentally abused as students of the Indian

Residential Schools in which The United Church of Canada was

involved, I offer you our most sincere apology. You did nothing

wrong. You were and are the victims of evil acts that cannot

under any circumstances be justified or excused.

We know that many within our church will still not

understand why each of us must bear the scar, the blame,

for this horrendous period in Canadian history. But the

truth is, we are the bearers of many blessings from our

ancestors, and therefore, we must also bear their burdens.

Our burdens include dishonouring the depths of

the struggles of First Nations peoples and the richness of

your gifts. We seek God's forgiveness and healing grace as we

take steps toward building respectful, compassionate, and

loving relationships with First Nations peoples.

We are in the midst of a long and painful journey as

we reflect on the cries that we did not or would not hear,

and how we have behaved as a church. As we travel this

difficult road of repentance, reconciliation, and healing, we

commit ourselves to work toward ensuring that we will never

again use our power as a church to hurt others with attitudes

of racial and spiritual superiority.

We pray that you will hear the sincerity of our words

today and that you will witness the living out of our

apology in our actions in the future.

The Right Rev. Bill Phipps

Moderator of The United Church of Canada

October 1998

Appendix 3

United Church-run Schools

Appendix 4

Project of Heart

Schools and church schools throughout Canada are using

the Project of Heart curriculum to help this generation

learn about the history of Canada.

Project of Heart is an educational tool kit designed

to engage students in a deeper exploration of indigenous

traditions in Canada and the history of Indian

residential schools. It is a journey for understanding through the

heart and spirit as well as through facts and dates.

Project of Heart was started by Sylvia Smith, a

teacher in Ottawa, Ontario. She wanted to commemorate the

lives of the thousands of Indigenous children who died as a

result of the residential school experience. Elders from

First Nation, Metis, and Inuit communities become regular

participants in classroom presentations and discussions.

Some classes also invite church representatives to share

their knowledge of how and why the churches helped to run

the schools and to talk about the Apologies.

To learn more about the project, videos and a list of

recommended resources, please visit:

The Authors

Stanley McKay was born on Fisher River Reserve, a Cree community. He

attended Birtle Indian Residential School, then went to Teachers College to

become a teacher. Later he went to the University of Winnipeg to obtain a

degree in Theology and worked with the United Church of Canada. He was

Moderator from 1992 to 1994. He is married, with three grown children and enjoys

fishing in the creek with his three grandchildren.

Maggie McLeod is a Cree woman from the Treaty 4 area (Peepeekisis First

Nation) She grew up in Saskatchewan, then moved to Saugeen Ojibwa

Territory (Ontario) where she raised daughters Nancy and Natasha.The United

Church of Canada has been important in Maggie's life. She is an intergenerational

survivor of the residential school system. Maggie's father Wilfred Dieter

attended File Hills Residential School and his parents, Fred Dieter and Marybelle

Cote, attended Regina Industrial School. Maggie loves to spend time with her

grandchildren Whitney, Isaac, Cayson, and Jack, and take long walks with her camera.

Bill Phipps grew up in Toronto, Ontario. He became a lawyer, teacher,

minister and served the United Church in Toronto, Edmonton and Calgary. He was

Moderator from 1997 to 2000. He loves canoeing, the Blue Jays, hiking, and

reading. He's active in Climate Justice, Right Relations, Calgary Peace Prize. He

enjoys playing catch with his children and grandchildren who live in Yellowknife,

Winnipeg and Toronto. www.billphipps.ca

Carolyn Pogue grew up on a farm near Toronto, Ontario. She is the author of

15 books for children, teens and adults. She is part of a group of women in

The United Church working to end child poverty. She loves canoeing, camping

and making art with Michael, Kate, Tristan, Foster and other kids. She writes a

blog for The United Church Observer. She lives in Treaty 7

territory. www.carolynpogue.ca

Thanks to:

The students and teachers at Sarah Thompson Elementary School,

Langdon, Alberta, and Glenbow Elementary School, Cochrane, Alberta

for compassionate listening and wise questions.

Reverend Cecile Fausak and Dot McKay.

General Council staff and The Archive at the United Church of Canada.

The staff at Wood Lake Publishing, who know how to fast dance.

WOOD LAKE PUBLISHING

Imagining, living and telling the faith story.

WOOD LAKE IS THE FAITH STORY COMPANY.

It has told:

The story of the seasons of the earth, the

people of God, and the place and purpose of faith

in the world

The story of the faith journey, from birth

to death

The story of Jesus and the churches that

carry his message.

Wood Lake has been telling stories for more

than 30 years. During that time, it has given form

and substance to the words, songs, pictures and

ideas of hundreds of storytellers.

Those stories have taken a multitude of forms

- parables, poems, drawings, prayers,

epiphanies, songs, books, paintings, hymns, curricula -

all driven by a common mission of serving those on the faith journey.

Wood Lake is proud of its long association

with the United Church of Canada. It has provided publication and learning resources to

hundreds of United Churches and has partnered with

UCC in the publication of the More Voices hymnal.

Editor and Proofreader: Ellen Turnbull

Designer: Robert MacDonald

Printing Production: Kailee Thorne

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

A catalogue entry for this book is available from Library and Archives Canada

Copyright © 2015 Maggie McLeod, Stan McKay, Bill Phipps & Carolyn Pogue.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced except

in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews

stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without

prior written permission of the publisher or copyright holder.

"Apology to First Nations Peoples (1986)" and "Apology to Former Students

of United Church Indian Residential Schools, and to Their Families and

Communities (1998)" are reprinted with permission of The United Church of Canada.

ISBN 978-1-77064-803-6

Published by Wood Lake Publishing Inc.

485 Beaver Lake Road, Kelowna, BC, Canada, V4V 1S5

www.woodlake.com | 250.766.2778

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada.

Nous reconnaissons l'appui financier du gouvernement du Canada. Wood

Lake Publishing acknowledges the financial support of the Province of

British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

At Wood Lake Publishing, we practice what we publish, being guided by

a concern for fairness, justice, and equal opportunity in all of our

relationships with employees and customers. Wood Lake Publishing is committed to

caring for the environment and all creation. Wood Lake Publishing recycles

and reuses, and encourages readers to do the same. Books are printed on

100% post-consumer recycled paper, whenever possible. A percentage of all profit

is donated to charitable organizations.

|

|

|